Does God Exist? A Look at the Evidence

What Kind of "Proof" Are We Talking About?

When people ask for "proof" that God exists, they often mean different things. This can make the conversation confusing before it even starts. The biggest disagreement isn't about the evidence itself, but about what counts as good proof.

Science vs. Philosophy

Today, many people think of proof in scientific terms. Scientific proof needs to be something you can test, repeat, and observe in the natural world. This method is great for studying how the material world works.

But asking for that specific kind of proof for God is like trying to measure love with a ruler. God is thought to be a non-physical being, so you can't put God under a microscope. By its own rules, science isn't set up to answer questions about the supernatural .

That doesn't mean we have no way to find answers. Philosophy and law use a different type of proof based on logic and finding the best explanation for all the evidence. Think of a courtroom trial, where a jury can't replay a crime. Instead, they look at all the evidence together to reach a decision beyond a reasonable doubt.

Can Science Explain Everything?

The idea that science is the only way to find truth is a belief called "scientism." But this idea has a big problem. The statement "only things proven by science are true" can't be proven by science itself.

It's a philosophical belief, not a scientific fact. This view unfairly ignores other ways of knowing, like logic, math, and morality.

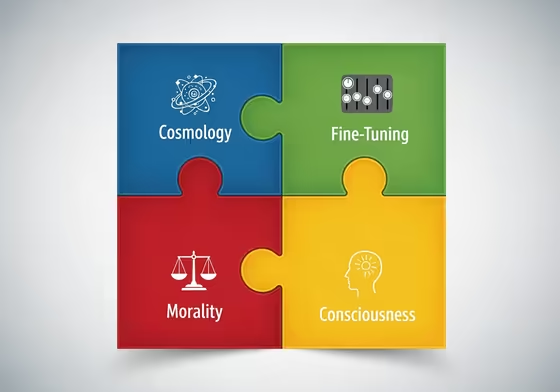

Building a Case for God

This article won't give you a single "100% proof" of God, because that's an unrealistic goal for such a big question. No one asks for 100% certainty for most things we believe about the world. Instead, we'll build a cumulative case.

The arguments that follow are like different clues all pointing to the same conclusion. No single clue tells the whole story. But when you put them all together, they can make a strong case.

Arguments for God's Existence

The "First Cause" Argument

One of the biggest questions is, "Why is there something instead of nothing?" The Cosmological Argument says that the universe's existence points to a powerful First Cause that started everything. A popular version of this is the Kalām Cosmological Argument.

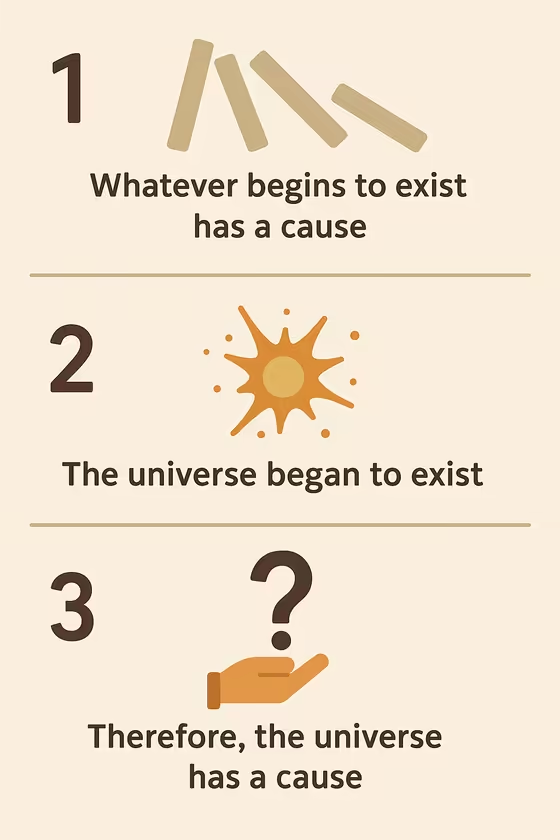

The Kalām Cosmological Argument

This argument, which comes from medieval philosophy , is simple and has three steps:

- Whatever begins to exist has a cause.

- The universe began to exist.

- Therefore, the universe has a cause.

The first point seems obvious. We know that things don't just pop into existence from absolutely nothing. To say something came from nothing is worse than magic.

The second point is backed up by both philosophy and science. They both arrived at the same conclusion from different directions.

-

Philosophical Reason: You Can't Have an Infinite Past

Think about it. If the past went on forever, we never would have reached today. An actual infinite number of past events leads to weird paradoxes, like a hotel with infinite rooms that is always full but can still take more guests. This suggests the past must have a starting point.

-

Scientific Reason 1: The Big Bang

In the 20th century, scientists found strong evidence that our universe had a beginning. Two main clues point to the Big Bang.

- The universe is expanding. In the 1920s, Edwin Hubble saw that galaxies are moving away from each other . If you rewind this process, everything comes back to a single, tiny point about 13.8 billion years ago.

- There is leftover heat. In 1964, scientists discovered a faint glow of radiation all over the sky, called the Cosmic Microwave Background . This is the "afterglow" from the hot, dense beginning of the universe.

-

Scientific Reason 2: The Universe is Winding Down

Another scientific principle, the Second Law of Thermodynamics , also points to a beginning. It says that in a closed system like the universe, usable energy always decreases over time. If the universe had existed forever, it would have run out of energy by now.

Since both points are well supported, the conclusion follows: the universe has a cause. This cause must exist outside of space, time, and matter. This means it must be timeless, spaceless, uncaused, and incredibly powerful.

Common Questions About the First Cause

The most common question is, "If everything needs a cause, what caused God?" This question misunderstands the first point. The rule is that whatever *begins to exist* needs a cause.

By definition, God is a being that did not begin to exist . God is seen as the necessary, uncaused being that started the chain of causes.

Another question involves quantum physics. Some people say that particles can pop into existence from nothing. But the "quantum vacuum" they talk about is not true nothingness. It's a physical field with energy and laws, so it's very much a "something."

Finally, some ask if this First Cause is a personal God. Think about it: how can a timeless, unchanging cause create a universe that changes and exists in time? An impersonal force would have created an eternal, unchanging universe. The only way to get a new effect from a timeless cause is if that cause made a choice, which points to a personal being with free will.

The "Design" Argument

This argument looks at the character of the universe. It says that the complex order we see around us is better explained by an intelligent designer than by random chance. While old versions of this argument used a watchmaker as an example , modern arguments focus on physics and biology.

Design in Biology

One of the biggest discoveries in biology was the code inside DNA. DNA is like a complex computer program that stores and reads information. In our experience, complex and specific information always comes from a mind.

The idea that this information could write itself through random chemical reactions has never been observed. So, the existence of this code is strong evidence for an intelligent source.

A Finely-Tuned Universe

The strongest design argument comes from physics. Scientists have found that the basic laws and numbers of our universe are perfectly balanced for life to exist. If any of these values were even slightly different, the universe would be a place where life was impossible .

This "fine-tuning" isn't a religious claim; it's a mainstream finding in physics. For example, if the force of gravity were a tiny bit stronger, stars would burn out too quickly for life to develop. If it were a tiny bit weaker, stars and planets would never have formed in the first place.

| Physical Constant / Quantity | Consequence of Slight Alteration |

|---|---|

| Gravitational Force Constant (G) |

Slightly Stronger:

Stars burn too hot and fast for life.

Slightly Weaker: No stars or planets would form . |

| Strong Nuclear Force |

Slightly Stronger:

No hydrogen, so no star fuel or water.

Slightly Weaker: Only hydrogen could exist; no other elements. |

| Cosmological Constant (Λ) |

Slightly Larger:

Universe expands too fast for galaxies to form.

Slightly Smaller: Universe would have collapsed back on itself . |

| Ratio of electron to proton mass | If slightly different, the building blocks for life, like DNA, could not form . |

This extreme precision needs an explanation. The chances of it happening by accident are so small they are hard to imagine. The most reasonable conclusion is that the universe's constants were intentionally set by a cosmic Fine-Tuner.

Common Questions About the Design Argument

One old objection comes from the philosopher David Hume. He said we can't compare the universe to a watch because we've never seen a universe being built. But this point is aimed at an outdated version of the argument. The modern argument is based on the data of physics, not a simple analogy.

Another objection is that evolution is the "blind watchmaker" that creates the appearance of design. But evolution can only work once life and the laws of physics already exist. It doesn't explain where the universe, its fine-tuned laws, or the information in DNA came from in the first place.

Some people bring up the "Anthropic Principle," saying, "Of course the universe is fine-tuned for us; otherwise, we wouldn't be here to notice." But this doesn't explain *why* it's fine-tuned. It’s like a prisoner surviving a firing squad of 100 expert shooters and saying, "Well, if I hadn't survived, I wouldn't be here to wonder about it." It doesn't explain *why* they all missed.

The main alternative idea is the multiverse. This theory suggests there are countless other universes, and we just happen to live in the lucky one where the conditions were right. But the multiverse is a metaphysical guess, not a scientific theory, because it can't be tested.

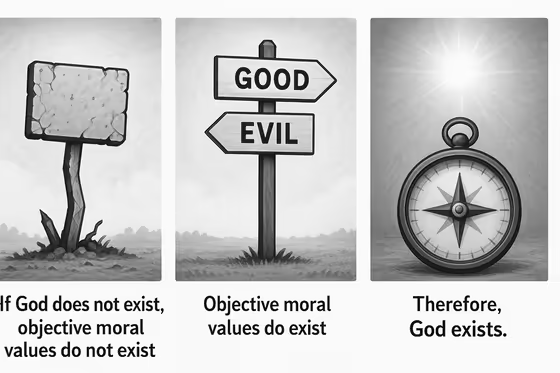

The "Morality" Argument

This argument suggests that our sense of objective morality points to a Moral Lawgiver. It's not about whether people can be good without believing in God. It's about where our ideas of "good" and "evil" come from.

The argument goes like this:

- If God does not exist, then objective moral values do not exist.

- Objective moral values do exist.

- Therefore, God exists.

First, we need to know the difference between subjective and objective morality. Subjective morality is based on opinion, like saying "vanilla ice cream is the best." Objective morality is a truth that is real whether anyone believes it or not, like "torturing children for fun is wrong."

If there is no God, then morality is just a human invention to help us survive. It wouldn't have any real authority. The argument is that we all know deep down that some things are truly wrong, which means an objective standard must exist.

If objective moral laws exist, they must come from a source outside of humanity. Since these laws are about how persons should act, it makes sense that they come from a personal source: a Moral Lawgiver.

Common Questions About the Morality Argument

A classic objection is the Euthyphro Dilemma. It asks, "Is something good because God commands it, or does God command it because it is good?" This presents a false choice.

The answer is that morality isn't based on God's commands but on his unchanging, good nature. God doesn't decide what is good; he *is* the standard of good.

Another point is that evolution can explain our morals. Evolution might explain *why we feel* that helping others is good. But it can't explain why we *ought* to be good, even when it doesn't help us personally.

The Argument from Consciousness and Experience

This argument suggests that our own minds and awareness are good evidence for God. If the world was only made of matter, it's hard to explain consciousness.

Why Are We Aware?

This is often called the "hard problem of consciousness." Science can explain how the brain processes information, but it can't explain why we have a first-person, inner experience. It doesn't explain what it's *like* to be you, see the color red, or feel happy.

This inner world of awareness doesn't seem to be physical. If materialism can't explain consciousness, then it's an incomplete view of the world. The best explanation for our finite minds is the existence of an infinite, foundational Mind.

What About Spiritual Experiences?

Throughout history and across all cultures, millions of people have reported having personal religious or spiritual experiences. According to the Principle of Credulity , we should generally trust people's experiences unless there's a strong reason not to. The huge number of these reports serves as evidence that people are experiencing something real.

Common Questions About These Experiences

Some say these experiences are just hallucinations or wishful thinking. While some might be, it's unlikely they all are. Studies have shown that genuine spiritual experiences tend to make people's lives better , unlike psychotic episodes.

Others argue that we can trigger these experiences by stimulating the brain's temporal lobe. But finding a neural link doesn't mean the experience isn't real. That could just be the physical mechanism God uses to communicate with us.

The toughest objection is that different people have contradictory experiences. A Christian might experience Jesus while a Hindu experiences Brahman. This is a good point, but it doesn't prove that all experiences are false. It could mean people are interpreting the same reality through their own cultural lenses.

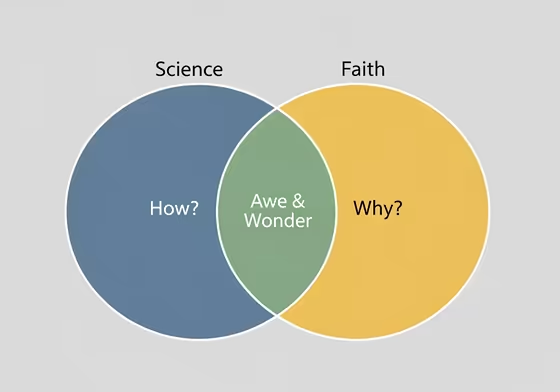

Science and God

Does Science Disprove God?

Many people think science and religion are in conflict, but this is a misunderstanding. Science is a method for studying the natural world. Since God is by definition supernatural, science can't prove or disprove his existence .

Science is great at answering "what" and "how" questions. But it isn't designed to answer "why" questions, like "Why do we exist?"

Can You Believe in God and Be Rational?

Faith and reason are not enemies. Faith isn't a blind leap in the dark. It's a reasonable trust based on evidence and experience.

Weren't Famous Scientists Religious?

The idea that science leads to atheism is historically false. Many of the founders of modern science were devout believers. They studied the universe because they believed a rational God had created an orderly world that they could understand.

This list includes scientists like:

- Nicholas Copernicus

- Johannes Kepler

- Galileo Galilei

- Robert Boyle

- Blaise Pascal

- Isaac Newton

- Michael Faraday

- Gregor Mendel

- James Clerk Maxwell

Can We Calculate the Odds of God Existing?

Some philosophers have tried to use a mathematical formula called Bayes' Theorem to argue for God. It's a way of showing how evidence can make a belief more or less likely. But this approach has a major flaw.

The final result of the calculation depends entirely on the starting number you plug in. An atheist can start with a very low probability for God, while a believer can start with a high one, and both will get the result they expected. So, the math doesn't really resolve the debate; it just reflects the person's existing bias.

Putting It All Together

The case for God isn't based on one single argument. It's based on how well different pieces of evidence fit together to explain the world we live in.

Which Explanation Makes More Sense?

To explain reality without God, you have to believe several unlikely things. You have to believe the universe popped into being from nothing for no reason. You have to believe its perfect fine-tuning is just a lucky accident, possibly explained by an infinite number of unseeable universes. You also have to believe that right and wrong, and even your own consciousness, are just illusions produced by matter.

Theism offers a single, simple explanation for all these things. A personal, intelligent, and good God explains the beginning of the universe, its fine-tuning for life, our sense of morality, and our consciousness.

Evidence vs. Faith

The goal of these arguments is to show that believing in God is a rational choice, not a blind one. They can provide a solid foundation for belief. But there is a difference between agreeing that God likely exists and having a personal faith and trust in him.

Why Does This Matter?

Believing in God can change how you see everything. It offers a foundation for meaning, purpose, and hope. It suggests that our lives are not accidents and that there is an ultimate standard for good and evil.

Ultimately, the evidence suggests that belief in God is a rational and coherent way to make sense of the world.